I first started using the MBTA in 1977, commuting to Boston College. Up through high school, I’d been dependent on either walking, getting a ride from my parents, or the very limited Canton-Mattapan bus line. I still remember my first trip over to BC that summer, checking out the route to school. The rapid transit line wasn’t very rapid, and the very decrepit PCC streetcar to BC was slow, dirty, bumpy and noisy. I distinctly remember being alarmed by the wheel squeal as we went through the curves in the subway.

But the MBTA opened up new worlds for me. I could get around on my own now. And as I learned to navigate it, I became a railfan. The Boeing Light Rail Vehicles were just being introduced, and I loved them. They were modern, clean and good looking, and if they were a little unreliable, well, they were new. Park Street Station was in the middle of renovations. I started reading up on the history. And at some point, I noticed that the subway widened out between Arlington and Boylston.

I gradually realized this widening was unusual – most of the Green Line is a two track tunnel, with no space between it. This area is quite wide, with some stub end tracks in the middle, and a lot of empty space. Because it’s wide, underground and unusual, I dubbed the area “Great Cavern”. But why does it exist? The answer starts with the original opening of the subway.

The Public Garden Incline

The Green Line was not originally a “line”, per se. It was simply a short length of tunnel designed to get all the streetcar lines off the street in the heart of downtown Boston. Tremont Street, where all the lines converged, had become incredibly congested. The solution was to put the streetcars underground. Construction started in 1895, and the first section ran under Tremont Street to the corner of Boylston, including Boylston Station, and then down Boylston Street to the Public Garden, where it veered out of the street and up an incline beside the street within the Garden itself. That incline would become the first part of Great Cavern.

The Boylston Street Subway

The original Tremont Street subway was a great success. It was one of those public works projects that really did what it was supposed to do – reduce congestion – and it helped spur a round of additional subway building. In 1911, the Legislature approved the building of the Boylston Street Subway. The subway was to be built from the junction of Commonwealth Ave and Beacon street, under the Muddy River, then going east along Boylston street to the corner of Tremont street… and there things got unclear. The legislation contemplated an additional two track tunnel under Tremont Street, or adding two more tracks to the Tremont Street tunnel. There were proposals from the Legislature to extend the new subway to Post Office square.

The Boston Transit Commission coped with the uncertainty by building the western sections of the new subway first, but by 1913, got permission to suspend work on the Tremont Street section of the new subway, and “temporarily” connect the Boylston Street Subway to the existing Tremont Street subway. That temporary connection remains today.

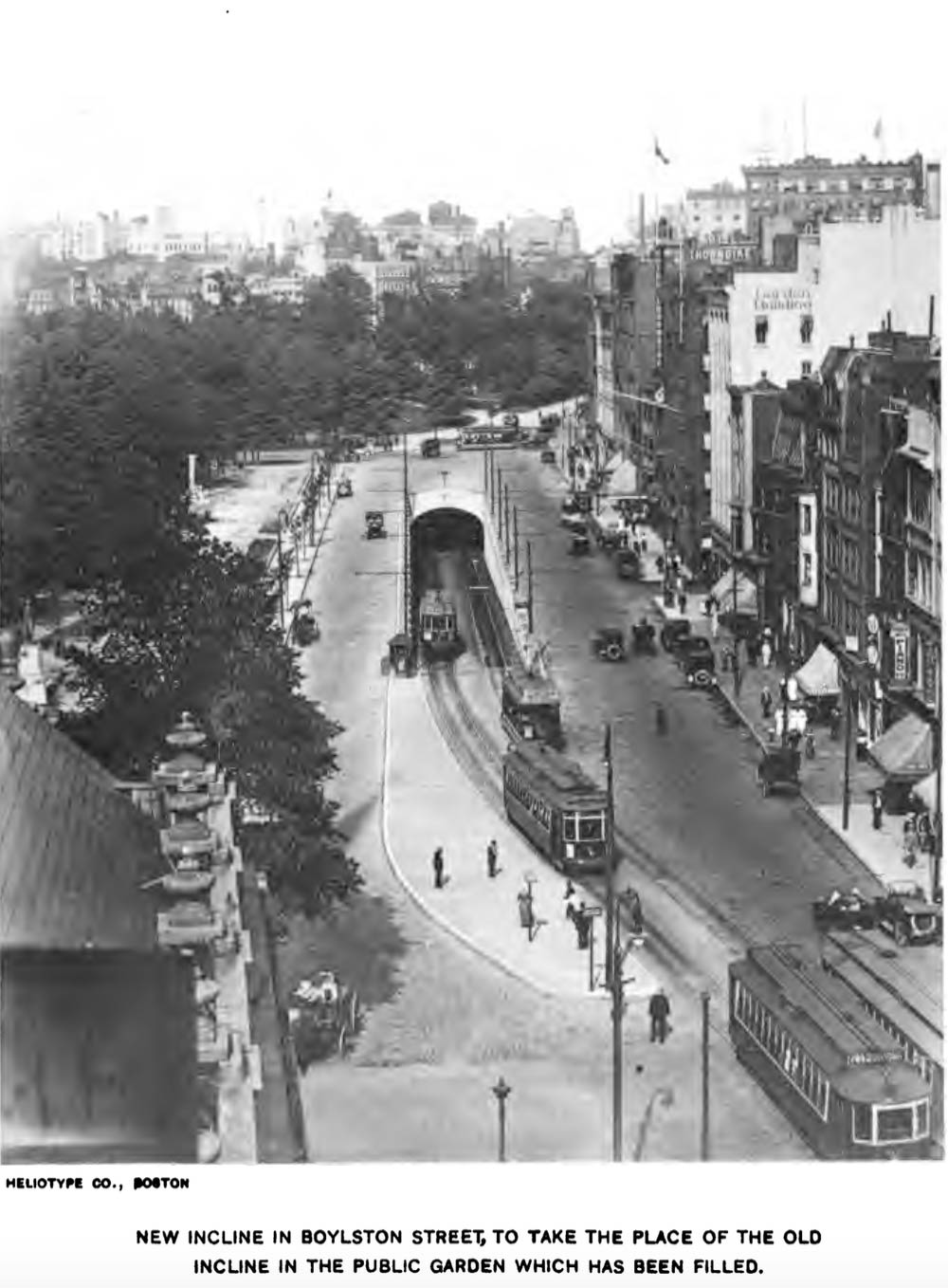

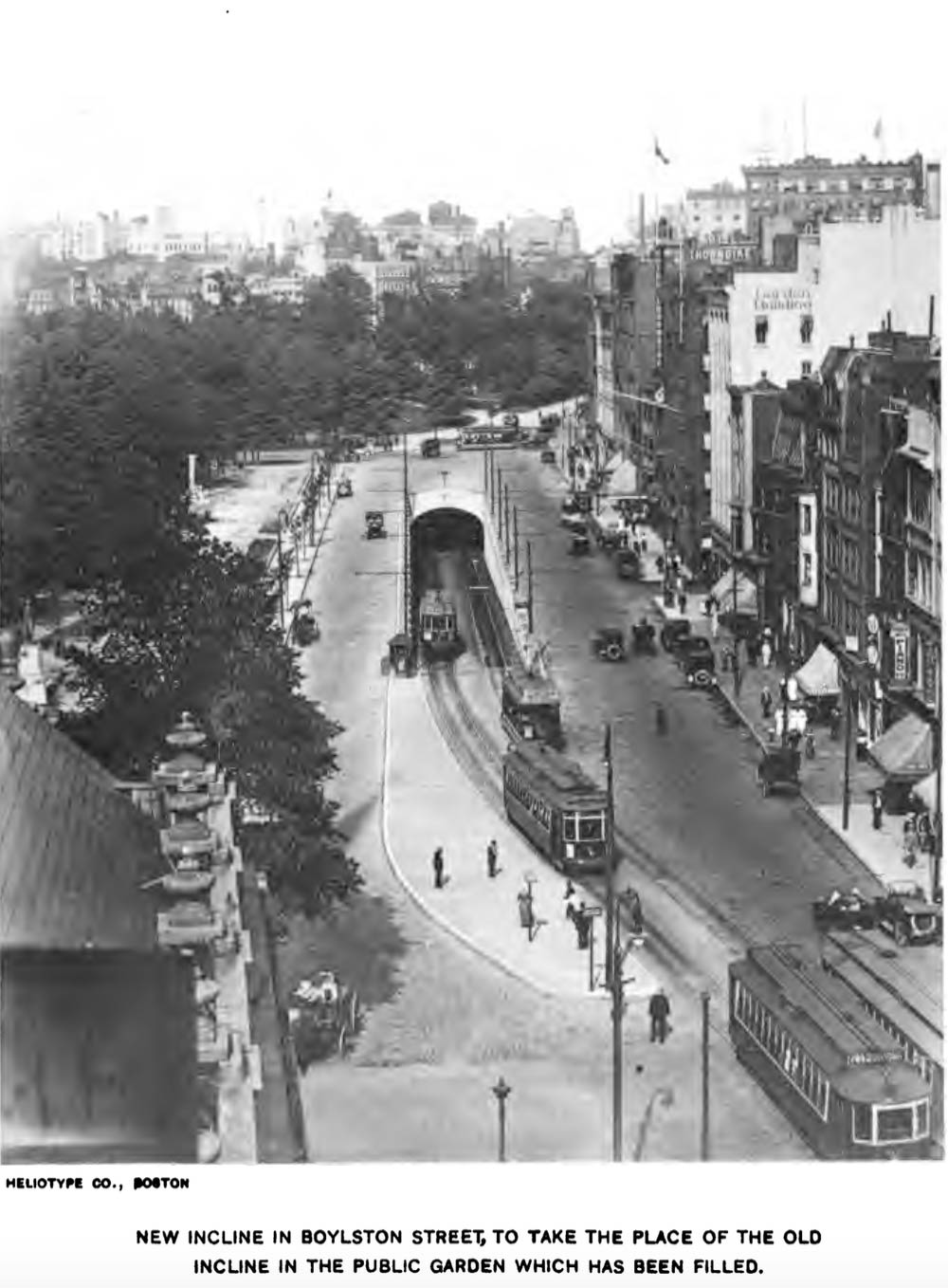

Keeping the original Public Garden incline would have required a “grade crossing” – outbound subway Boylston street traffic would have crossed over the inbound surface track, something that the engineers of that day sought to avoid at all costs. And yet, an incline was still necessary at that location, because streetcar traffic from Huntington Avenue would still be surface-running, and needed to enter the subway there. The solution was to widen Boylston street at that point, seal off the original Public Garden incline, and build a new incline in the middle of Boylston Street, between the inbound and outbound tracks. Enough of the original incline was left underground to act as a siding for car storage.

1914 Boylston Street Incline. From the 1915 Boston Transit Commission Report.

The Transit Commission chose to deal with the Post Office Square question by deferring it; the Dorchester Tunnel (Red Line) was already under construction and the commission felt that the new tunnel would change traffic patterns; instead it was decided to enlarge Park Street Station.

The final part of the story came in 1941, with the building of the Huntington Avenue Subway. Streetcar traffic was rerouted from the surface of Boylston Street to the new subway, rendering the Boylston Street incline unnecessary. It was sealed off, leaving the large cavern we see today. The MBTA still uses the stubs of the tracks that once led to the surface for equipment storage.