The MBTA is in the process of adding 24 new streetcars, called the Type 9, * for the Green Line for the extension to Somerville. The first one, #3900 went into revenue service in December, and I’ve been wanting to ride one since.

A gentleman by the name Stefan Wuensch has created a site showing real time location data of each train on the system, and I’ve been monitoring it to see if I could see #3900 running. Yesterday, it was running on the B line with #3902, and I decided to head into town.

I got to Riverside, and checked the site again. #3900 was inbound from BC, and I was curious to see whether we would get to Kenmore before or after it. The B line is shorter, but also slower. As we approached Fenway on the D Line, I could see it approaching Blandford Street on the B. As the lines merged at Kenmore, it was one train ahead of us.

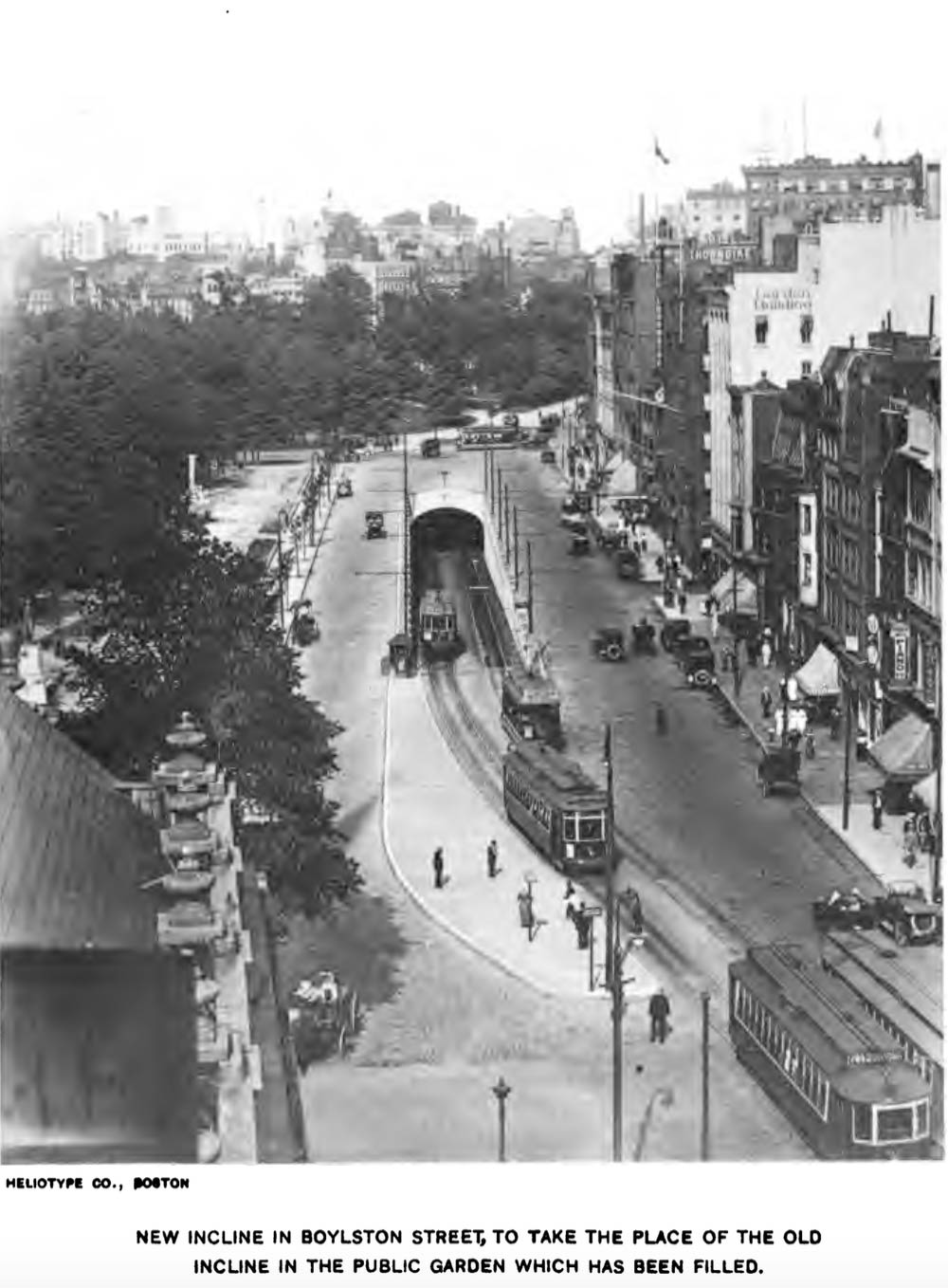

I saw that the Type 9 train was terminating at Park Street. I decided I wanted to see if I could take it back outbound. Decisions, decisions. Do I take my train all the way to Park Street, and hope it takes some time to turn the Type 9 around, allowing my train to catch up, and allowing me to board an empty train? Or do I get off at Boylston? That way, even if the train is turned around fast, I’m still going to be ahead of it. It also means I will have to pay to re-enter on the outbound side, and possibly getting onto an already crowded train. I decided to get off at Boylston, walked fast past the old PCC and Type 5 parked on the outside inbound track, up to the Common and back down to the outbound platform.

First up was a Type 8/7 combo bound for the B Line and Boston College. “Great,” I thought. “The Type 9 will be less crowded. The train loaded, and left, and I saw the the next train approach. It was the Type 9, and it was now signed for the C Line. “Great,” I thought. “It’ll be easier to get back to the Riverside line”. As the trolley pulled into the station, I grabbed my phone, and took its picture.

And then it continued on, without stopping. Curses, foiled again.

* The MBTA uses the same “Type” nomenclature to designate models of Boston streetcars that its predecessor, the Boston Elevated Railway, did. Types 1 – 5 were Boston Elevated models, dating from the early 1900s up to the early 1950s, before going to an industry standard streetcar, the PCC streetcar in the 1940s. When it came time to replace the the PCCs, they prototyped a Type 6 car before going with the US Standard Light Rail Vehicle, manufactured by Boeing. When the Boeing LRV failed to live up to expectations, the T went with a custom design, the Type 7, which is still in service, along with the Type 8 cars, which are a “low floor” car designed for wheelchair accessibility.↵